This Much Is True Alan Ball's True Blood for HBO

By Gina Piccalo For Emmy.

Issue No. 3, 2010

To consider Alan Ball's career is to confront one remarkably successful leap of faith after another.

He started in theater, writing satiric odes to his vision of the South. He got pulled into the sitcom gulag. And as catharsis, he wrote a heartbreakingly cynical spec script that caught Steven Spielberg’s eye and then became an Oscar-winning film. From there, he created a Primetime Emmy-winning TV show set in a funeral home, of all places, and sold a pilot about Southern vampires that has become one of HBO’s most watched shows since The Sopranos.

But ask him about his next act — no, a phenomenal hit on HBO hasn’t stopped him from planning ahead — and Ball’s adventuresome spirit becomes especially evident. He’s considering a screwball comedy set in the 1930s and maybe even a character-based sci-fi project. And he’s committed to telling these stories on TV.

Movies, Ball points out, aren’t the best medium for his brand of narrative. “I’m not writing for fifteen-year-old boys,” he says on a quick break from shooting season three of his vampire drama, True Blood. “I’m interested in adults grappling with trying to make their lives meaningful and authentic. I don’t think people want to make movies about that.”

There’s no question that Ball’s voice — as committed to moral ambiguity as it is to operatic sensitivity and romance — has helped drive TV storytelling to some interesting new places.

“It’s confrontational and it’s often clearly challenging the audience,” says Ball’s longtime friend and collaborator Nancy Oliver, now coexecutive producer on True Blood. “There’s a mix of sensitivity, melodrama, aggression and humor that I admire. And that’s all tempered by the humor and emotion he carries. He has a very keen sense of mortality — and what it’s like to be a human being living with that sense all the time.”

Here are a few things not everyone knows about Ball: He has 10,000 songs on his iPod. In college he played keyboard in a new-wave band. He watched two seasons of ABC’s The Bachelor before he turned off reality TV for good. And he named one of the Six Feet Under corpses after the ABC executive who once canceled his sitcom.

It’s fitting that he started life in the South, one of the great American breeding grounds of biting wit and black humor. Ball, fifty-three, was born in Marietta, Georgia, best known as the home turf of conservative former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich. He put on shows with the neighborhood kids and devoured film. But he didn’t consider entertainment a career option until his first year at Florida State University in the late 1970s.

At the time, Ball wanted to act. And so did fellow student Oliver. They both auditioned for a school production of Picnic. He read as the villain, she as the ingénue. Neither was cast. But their friendship took root and so did their drive to write and produce their own material.

They started their own theater company, General Nonsense Theater, in Tallahassee, Florida. There, and later in Sarasota, they put on late-night musicals and performed sketch comedy, eventually producing a cable-access show.

Soon Ball ventured to New York, where he spent seven years working by day as a graphic designer and art director and by night as a playwright managing Alarm Dog Rep, the renamed theater group.

“I spent most of my twenties and the first half of my thirties just doing it for the love of my work,” Ball says. “Nobody got paid. We all had day jobs. I got very accustomed to doing something that was very organically satisfying and wasn’t shaped by the need to make money or the desire to be famous or any of those things. It was like working in a little bubble. I worked as writer, director, actor and that was the best education I could have ever gotten. When I got to Hollywood, it was very surprising.”

One of Ball’s plays, Five Women Wearing the Same Dress, about bridesmaids in Knoxville, Tennessee, made it to Off Broadway and landed him an offer from a Carsey-Werner Television scout. He was invited to join the second season of ABC’s Brett Butler vehicle, Grace Under Fire.

“I thought, ‘What’s the worst that could happen?’” he recalls, a tad sarcastically. He soon learned. After a year Ball went to another Carsey- Werner show, CBS’s Cybill. Things didn’t improve. Ball once likened those network years to “the gulag of Cybill and Brett Butler.” His main refuge was his American Beauty script. He banged it out in eight months, during furious after-work writing sessions.

“I spent two years on Cybill and they offered me so much money to write the third year,” he says. “I felt like such a whore and I was so frustrated, I would pour all my anger and frustration and hope and desire into this screenplay. If I hadn’t written that, I probably would have become a drug addict or developed some unhealthy destructive behavior.”

For Ball, the script was simply a cathartic exercise. He was still optimistic about sitcoms when he pitched what he considered a weird idea to ABC — and they bought it. Oh, Grow Up was about three aging college buddies, one of whom had recently come out as gay. But Ball soon realized he was still hamstrung creatively. The network gave him notes asking that he make everybody nicer and spell out the subtext.

“Both are really horrible notes,” he says. “Nice people are boring. Comedy, by the way, is mean at its heart. And articulating the subtext, that’s like not respecting your audience.”

Meanwhile, his agent, Andrew Cannava at UTA, started strategically selling American Beauty. In April 1998, right around Ball’s forty-first birthday, Spielberg optioned it for DreamWorks. A year later Oh, Grow Up was canceled after its first season, but the disappointment was dwarfed by the phenomenal success of American Beauty. By spring 2000, the film had won five Oscars, including best picture and best original screenplay. That’s when HBO came calling.

Ball kicked around ideas with Carolyn Strauss, then HBO’s president of entertainment, and found they both loved Tony Richardson’s satire The Loved One, a 1965 film based on the 1948 Evelyn Waugh novel of the same name.

“They talked about exploring issues of mortality,” says Michael Lombardo, HBO’s president of programming and West Coast operations. Ball went home to Georgia for two weeks — without a deal in place — and returned with a pilot script.

“We were stunned,” Lombardo says. “It did all the things we’d hoped, in the sense of exploring the bigger themes, and did it in the most entertaining and funny and moving way. That’s the beauty of Alan Ball’s writing.”

For Ball, launching the new series was a bit harrowing. “Six Feet Under was a film school,” he says. “I had only worked on sitcoms. That’s a completely different beast. I had been allowed on the set on American Beauty as an observer. But I didn’t know what I was doing.”

The show debuted on HBO in June 2001 with a prescient melancholy. And perhaps that’s why it took a season — and the discombobulating aftermath of 9/11 — for the show’s dark sensibility to be fully embraced by critics. The New York Times, for one, declared the initial episodes as “sleazily mendacious” rife with “overriding smugness.”

Everyone came around eventually. In its first season the show earned six Primetime Emmys and two Golden Globes, including an Emmy for Ball as outstanding director for a dramatic series and a Globe for best dramatic TV series. By summer 2002, Salon.com was heralding it “remarkable,” while even the New York Times conceded it was “ostentatious with its passion.” The series went on to win three more Emmys and another Golden Globe before its final bow in 2005.

When Ball ended Six Feet Under — sending his main characters into the afterlife in one of TV’s most memorable and transcendent series finales — he also left the genre behind. “I’m kind of done with the existential drama,” he now declares.

After the weighty narrative of Six Feet Under, Ball was looking for something lighter. He settled on a couple of stories: Alicia Erian’s 2005 coming- of-age novel Towelhead, about a thirteen-year-old Lebanese-American girl troubled by her precocious sexuality, and Charlaine Harris’s series of Southern Vampire Mysteries. The Harris series had already been optioned for a film. So while Ball waited for the option to expire, he wrote, directed and produced Towelhead on an indie budget, landed a stellar cast with Aaron Eckhart, Maria Bello and Toni Collette, and took it to the Toronto and Sundance film festivals.

When the time came, he snapped up Harris’s vampire stories and set about convincing the author that they would be best adapted for television.

“I got on the phone with Charlaine and said, ‘Here’s what I love about these books. Here’s what I would do. It’s too big and too rich and too interesting for a movie.’ Sensibility-wise we were in the same ballpark. Charlaine’s books walk a fine line between satire and tragedy and comedy and drama, romance and sexuality. I’m from the South. It felt very authentic to me.”

Harris was sold.

Around the time of the show’s September 2008 premiere, HBO was still smarting from the loss of Six Feet Under and The Sopranos. Hopes for the highly anticipated John from Cincinnati had swiftly died. And AMC’s Mad Men, which HBO had passed on, had just earned a raft of Emmys. There was a lot riding on True Blood, so the network launched an aggressive viral marketing campaign to generate buzz. Meanwhile, Harris’s formidable fan base worked up froth in the blogosphere as news trickled out about the cast.

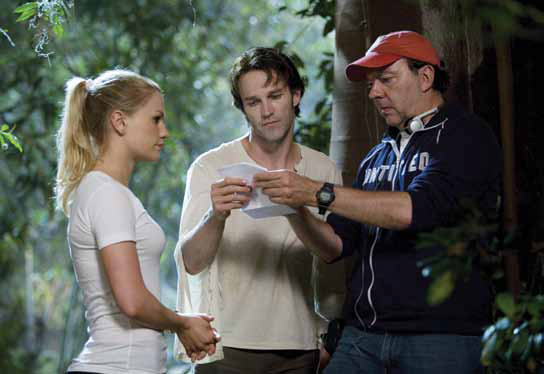

The Gothic Southern satire was thick with outrageous sex and abundant viscera, and critics lauded the show as a “romp and a wallow,” “a pungent political satire” that was “deliciously twisted.” It was an immediate hit. Ball used vampires as metaphors for the disenfranchised of every stripe and for what he once called “the terror of intimacy.” And the old-fashioned romance of Civil War–era vampire Bill and telepathic waitress Sookie Stackhouse turned into a real-life one as the stars who play them, Stephen Moyer and Anna Paquin, announced their own love story.

By the second season, Ball was infecting the Harris storyline with his own delicious spin. Goblin ladies, shape-shifters, anti-vampire fanatics, orgies and vampire love triangles ran wild.

“True Blood started out as a fairly contained world with this little vampire love story,” says Alan Poul, a friend of Ball’s and an executive producer on Six Feet Under. “He’s taken it and run with it. It’s so out there now. It’s this incredible vision of the entire world run amuck.”

What Ball has called “popcorn for smart people” is now one of HBO’s most successful shows. The third season premieres June 13. Ball has already promised a fourth.

So far, the first two seasons coincide with Harris’s first two books. But there are nine volumes in the series, with four more on the way. The TV show couldn’t keep up with the book series without a serious plot problem: aging vampires. Besides, Ball isn’t convinced he wants to be a “fulltime showrunner” beyond a fourth season.

“That is a grueling job,” he says. “I love it. I’m still having a blast. I also know I’m not as young as I used to be.”

And, he says, there are always new stories to tell. “I just am a little leery about saying ‘This is what I’ll be doing for the rest of my life’ about anything.”